Dallas Foscue slowly walks his way down the hall, careful not to stumble, and he grabs at air as he tries to find one of the chairs positioned around his small kitchen table.Â

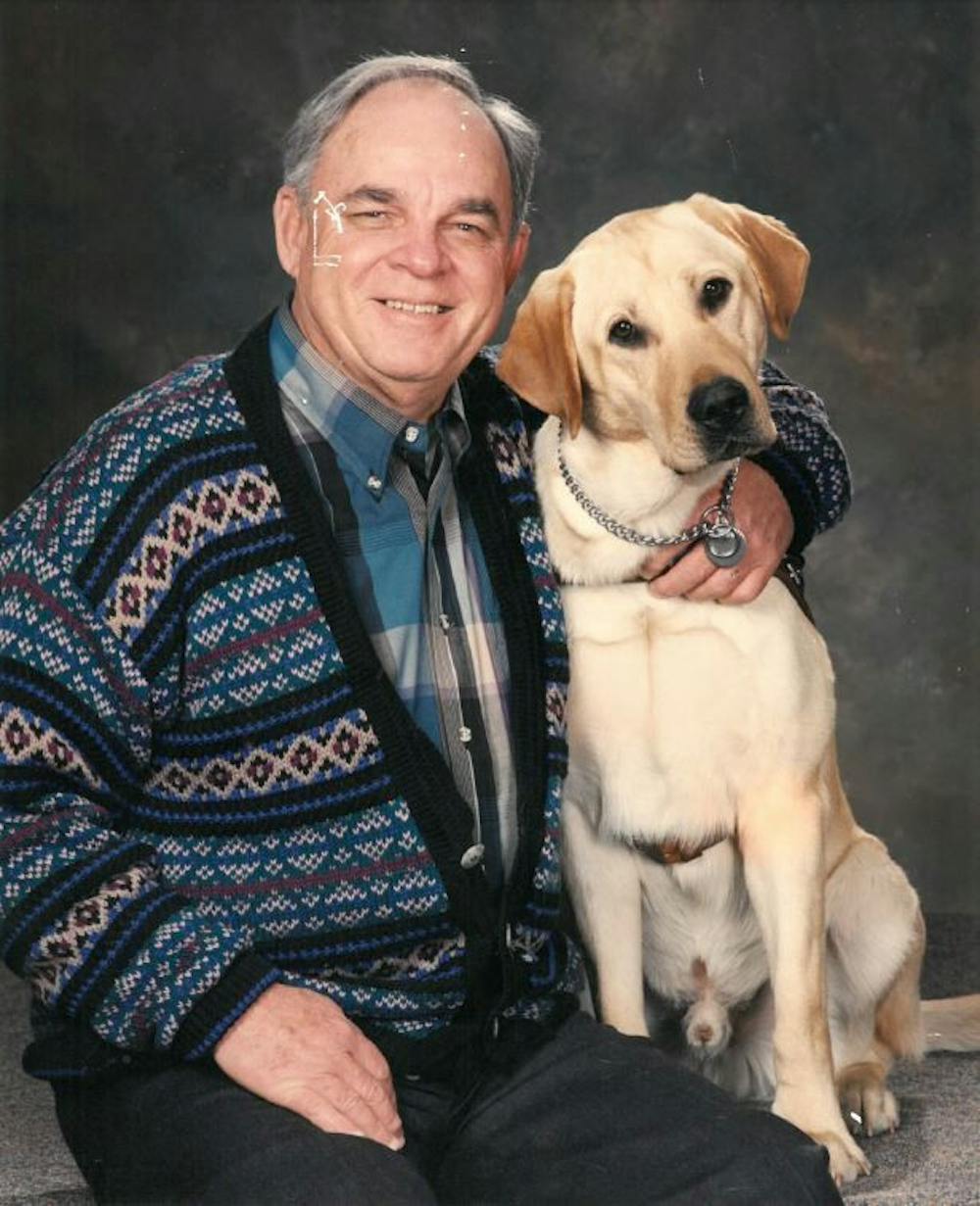

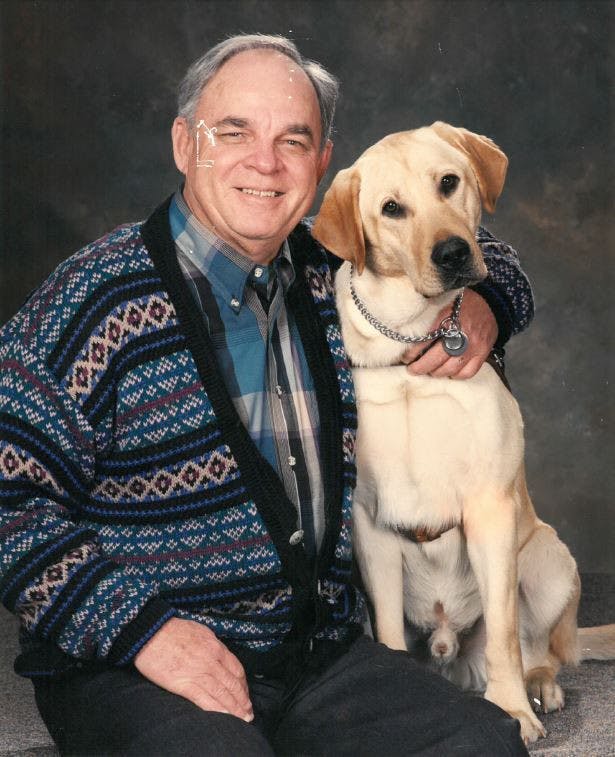

Foscue is 95 percent blind on a bad day, but in 1991, he found a lifeline as his vision faded — a faithful seeing-eye dog named Niblett. During that year, Dallas had lost 50 percent of his vision but was still living in a home independently with his wife.

Foscue is one of thousands of Americans who have at some point relied on a service animal to maintain their independence and mobility. When he was 28 years old, he was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosis, a degenerative disease that attacked his retinas. His doctor told him within five years his vision would diminish to total blindness. Now, at 86, his eyes are finally approaching complete blindness. But he rests easy knowing he was able to enjoy his vision, however limited, for the last five decades.

“God had other plans,†he said with a smile as he looked in the direction of the window.

Foscue has lost most of his depth perception as the disease has claimed more of his retinas. He is able to see shapes — but not much else. For instance, if a door is painted the same color as a wall, he is likely to struggle to find it.Â

Despite his rapidly declining vision and partial loss of hearing, he laughs often and enjoys occasionally making fun of himself. Part of his disease is a fluctuation of sight abilities that can vary from day to day. As he began losing his depth perception and ability to see in low light, it became evident if he wanted to maintain his independent lifestyle, he would have to seek help.

Dallas Foscue, whose vision faded in 1991, holds his seeing-eye dog named Niblett.

It was at this point he contacted his social worker who put him in contact with the Guided Eyes for the Blind, a group located in New York that specializes in training and matching service animals with disabled people in need. These service animals are highly trained and are only given to those who have the greatest need for them.

Foscue had to go to a specialized camp to learn how to work with his new service dog. By the time he was introduced to Niblett, the dog was already a fully trained service animal who knew exactly how to help him maintain his independence.Â

Foscue traveled to the Guided Eyes for the Blind center in Yorktown Heights, New York, in 1991, after an exhaustive screening process. He did not just arrive at the school and receive a dog. Instead, he had to train Niblett and himself. The institution did cover all of the expenses necessary for Foscue to obtain his seeing-eye dog, but they also required him to go through many levels of screening to ensure he was not impersonating a blind person and truly would benefit from having a service animal. The center had already spent $26,000 at least on the training of Niblett alone. Foscue was one of six disabled people flown to the facility to be go through training and ultimately receive a dog.Â

Each person went through several trials to identify each of their specific needs and disabilities so the center could be match each person with the animal who would be most fitting to help them.Â

This program lasted six weeks. For the first two weeks, the participants weren’t given a dog or even allowed to interact with any of the animals. On the third week, Foscue was introduced to Niblett. He remembers vividly the instant connection he felt with the dog. The rest of their time together at the center was spent not only teaching Niblett to listen to Foscue, but also teaching Foscue to listen to and to trust Niblett, an exhausting process.

“Sometimes it was worse than boot camp,†Foscue said.

For Foscue and many disabled people like him, his dog was more than just a guide — he was part of the family. Each night Niblett would sleep at Foscue’s side. At the end of the day when it was time to let Niblett relax, Foscue would remove his harness and take him to the back yard to throw a tennis ball into the lake behind the house. Niblett would try his hardest to catch it in midair. Foscue was not the only one who felt Niblett was part of the family — his children played with Niblett for hours when the dog wasn’t in his harness.

Niblett allowed Foscue to maintain his mobility and independence. Sadly, after 10 years of service, Foscue was forced to retire Niblett when he could no longer do his job. A year later Niblett passed away. Foscue never replaced Niblett as a seeing-eye dog. Instead, he moved with his wife into an assisted living facility and returned to using a cane to navigate unfamiliar terrain.

Foscue stands up slowly clutching tightly several newspaper articles about him and Niblett in his hand as well as the photo that had been sitting on the table. He looks down at it, even though it likely looks like little more than a rectangle with several colors, and forms his lips and whispers: “he was a good boy.â€