A Daily Helmsman investigation first in a two-part series

Are women professors at the University of Memphis paid less because they choose to teach in low paying fields? Are they paid less because women, overall, have been slower to earn advanced degrees and climb the academic ladder?

Or are they paid less because the deck is stacked against them?

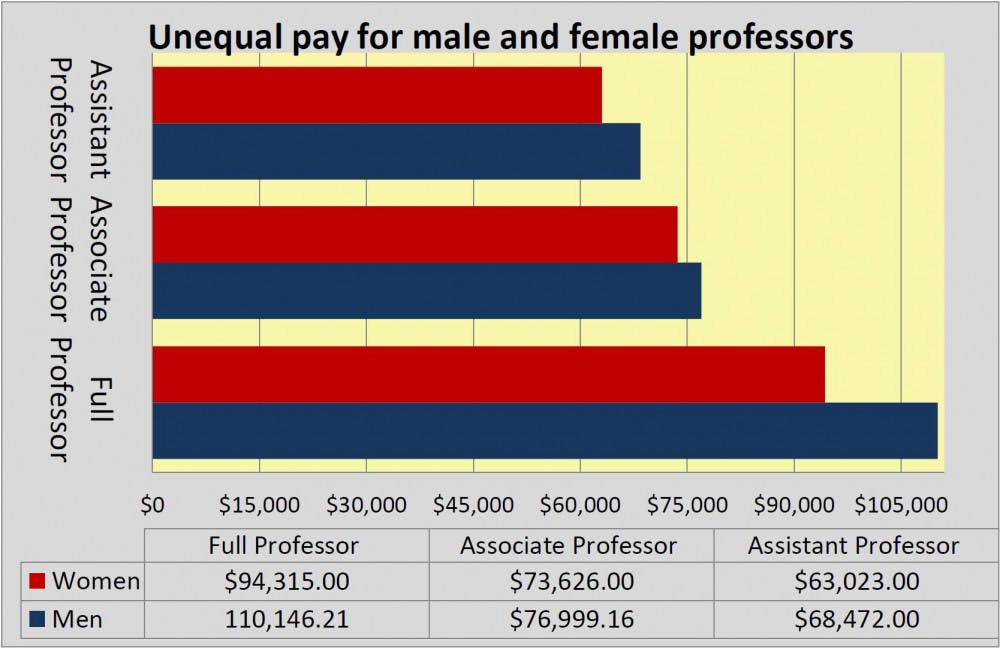

The U of M paid female full professors an average of 86 cents for every dollar a male professor made – or $15,830 less per year than the average of their male peers, according to an analysis of 2014 state salary data.

That is less than the national average. Women full professors from institutions across the country earned 88 cents for every full dollar men made, according to 2011 data from the American Association of University Professors, the latest available from that group.

The U of M’s gap appears to have grown in recent years for full professors. Memphis’s male full professors have seen their average salary increase by $10,000 since 2009, according to data from the Chronicle of Higher Education. During that same time period, the average salary for women full professors has stayed about the same.

“Gender equity is something you have to actively pursue and it’s been a university priority for a long time. It’s a challenge we have not yet overcome.” Tom Nenon, former university interim provost and current dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Memphis.

Less pronounced, but still significant, gender pay disparities exist throughout most of the U of M faculty ranks, according to an analysis of the Tennessee Board of Regents 2014 salary database done for The Daily Helmsman by copy editor Jonathan A Capriel.

For instance, at the associate professor level women were paid an average of 95 cents for every dollar earned by male associate professors – or about $3,373 less. At the assistant professor ranks, women made 92 cents or about $5,448.79 less.

“Gender equity is something you have to actively pursue and it’s been a university priority for a long time,” said Tom Nenon, former university interim provost and current dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Memphis. “It’s a challenge we have not yet overcome.”

[caption id="attachment_752" align="alignleft" width="1668"] Out of 214 full professors, only 40 were women at the University of Memphis in 2014. At the associate level there were 117 women and 135 men. Most assistant professors were women, out of 212 only 101 were men. This analysis used data from the Tennessee Board of Regents on the major colleges at the U of M. These numbers exclude deans, chairs of excellence and research professors. [/caption]

Nenon attributed gender pay disparities to several factors such as hiring dates, lack of turnover among tenured professors and the drying up of merit money. However, he acknowledges, “I’m not naïve to believe that there might not be other factors involved.”

Studies of university professors around the nation show major social inequities come into play in academic settings. For example, having children helps male academics but hinders women’s careers, according to researchers at University of California, Berkeley.

“For men, having children is a career advantage; for women, it is a career killer. And women who do advance through the faculty ranks do so at a high price. They are far less likely to be married with children,” Mary Ann Mason, professor and co-director of the Center for Economics & Family Security at Berkeley, wrote in an article for Slate.

“We also see many more women who are married with children working in the growing base of part-time and adjunct faculty, the “second tier,” which is now the fastest-growing sector of academia,” Mason said. “Unfortunately, more women PhDs has meant more cheap labor. And this cheap labor threatens to displace the venerable tenure-track system.”

Looking solely at average or median salaries can be misleading. The university’s professor gender-wage gap is complex. Several factors contribute to the overall disparity, Nenon said.

Less than a quarter of all U of M full professors are women. In the university’s biggest college, Arts and Sciences, only 17 of the 102 full professors are women.

[caption id="attachment_743" align="alignleft" width="1688"] Only 17 of the 85 full professors in the College of Arts and Sciences were women. At the associate level, the numbers were almost equal, 47 were men and 46 women. Only 28 of the 64 assistant professors were women. All graphs are based on the Tennessee Board of Regents 2014 salary data base. Only assistant, associate and full professors in the major colleges at the University of Memphis were looked at. The analysis excluded deans, chairs of excellence and research professors. [/caption]

These low numbers are historical anomalies, explained Nenon. Those who are in full professorships reflect who the university hired 12 years ago because it can take that long to move up the academic ladder, Nenon said. However, it can also be a result of who the university hired 40 years ago, Nenon said.

“Women were not encouraged to pursue doctoral degrees in years past,” he said.

Nenon said that he hasn’t been able to promote more women and won’t be able to until some veteran full professors retire. There is no mandatory retirement age at the university.

Female full professors in the College of Arts and Sciences pulled in an average salary of $86,122 in 2014 while men got $100,647.13.

However, Nenon said that female academics, overall, tended to specialize in fields that paid less such as social sciences and humanities, while male professors tended to be in hard sciences and business, which pay more. He said it’s important to compare salaries at the department level within the university’s colleges.

“Our highest paid professors (in Arts and Sciences) are in math and computer sciences,” Nenon said. “Those are areas that are filled with mostly guys. We have more women professors in English, where salaries are much lower.”

Excusing gender inequities in pay by saying that women choose fields that pay less is flawed logic, said Anna S. Mueller, assistant professor of sociology at the U of M.

“Choice is a really complicated thing,” she said. “Women face hostile environments in graduate school in male-dominated fields. So it’s not really their choice to leave if they've been bullied out.”

Mueller co-authored an extensive report on the gender pay gap at the University of Texas-Austin. In that study, she found women professors at all ranks were paid less than men.

While she did not look at the U of M’s wage gap, she has researched salary disparities between male and female professors at other public colleges. While women do tend to go into fields that pay lower salaries, “a lot of research shows that the wage gap is not about merit or productivity – it really is discrimination,” Mueller said.

In computer sciences at the U of M, there was only one woman in 2014, and she was an associate professor. She earned about $8,000 below the department average for associate professors, which was $98,065.

“Choice is a really complicated thing. Women face hostile environments in graduate school in male-dominated fields. So it’s not really their choice to leave if they've been bullied out.” Anna S. Mueller, assistant professor of sociology at the U of M.

Meanwhile, the average salary for the nine full professors in the English department was $78,906. Breaking down the averages by gender, the department’s four women full professors were paid $73,260; the five male full professors received an average salary of $83,422.

“The two highest salaries in the English department are both ex-chairs who are men,” Nenon said. Former chairs keep their administrative salaries even after returning to teaching.

Mueller’s study of salaries at UT-Austin showed that the pay gap between male and female assistant professors in Austin was much smaller than all other ranks, just like in Memphis and nationally. While some will say this is a sign things are getting better for women, Mueller is skeptical.

“This could be a sign of change in a positive way, but it could also mean that the gap develops over time,” Mueller.

How wide is the pay gap?

Memphis OTL’s analysis included 678 educators from the university’s major colleges who were either on tenure tracks or employed as clinical professors. Only those who the Tennessee Board of Regents (TBR) defined as assistant, associate and full professors were included. The analysis excluded deans, chairs of excellence and research professors.

Just over half of the 212 assistant professors the U of M employed in 2014 were women. They earned an average of $63,023 while their male peers were paid $68,478.

There were 252 associate professors in 2014, according to TBR’s website. The average salary for the 135 men across all disciplines was $76,999. Women earned an average of $73,626

“Making sure you have gender equity is something you have to actively pursue.” Tom Nenon

Only 40 of the university’s 214 full professors are women. Their average pay was $94,315; their male peers were paid an average of $110,146.21.

These numbers do not account for race, hiring dates or individual achievements such as degrees earned. Nor does this analysis distinguish between professors working a nine-month academic year or a 12-month year. However, university administrators said only a handful of professors worked year round.

Memphis gender gap persists for more than a decade.

Data collected from the Chronicle of Higher Education tracked the average salary for full, associate and assistant U of M professors from 2003 to 2013. Arranged by Memphis OTL" width="1024" height="749" class="size-large wp-image-766" /> Data collected from the Chronicle of Higher Education tracked the average salary for full, associate and assistant U of M professors from 2003 to 2013. Arranged by Memphis OTL[/caption]

Women full-professor pay at the U of M has been well below that of their male counterparts for at least a decade. The gap between men and women at the full professor level was narrowest in 2009, when women earned about $6,000 less than their male peers. Since then, the average pay for female full professors has remained stagnant while their male peers’ average salary continues to rise.

Data collected from the Chronicle of Higher Education tracked the average salary for full, associate and assistant U of M professors from 2003 to 2013.

At the full and associate level, the average salary for female professors was consistently under their male peers for an entire decade from 2003 to 2013, the most recent data available.

For one year, in 2006, male assistant professors at the U of M actually made as much as female associate professors, a rank above them.

The pay gap was narrowest between male and female assistant professors in 2010 and 2011, when the difference was less than $1,000 a year.

“Making sure you have gender equity is something you have to actively pursue,” Nenon said.

The university has tackled the gender pay difference a few times in the past. In the ‘90s, professors urged then-President Lane Rawlins to narrow the gender gap, Nenon said. “Rawlins took steps to address pay equity then.”

In the early 2000s then-President Shirley Raines and former Provost Ralph Faudree again took action to correct gender pay discrepancies.

“I know this because I was working under Ralph then,” Nenon said. “We didn’t wait for the faculty to step forward at that time. We took action on our own.”

But now, unlike in decades past, the U of M does not have the money to fix any type of pay disparities, Nenon said. Since 2007, the university has had no money to put toward merit-based raises.