Suicides among active-duty soldiers dropped in 2010 for the first time in five years, but the number of Army reservists and National Guard members who killed themselves nearly doubled, leaving Army officials scrambling to find ways to gain control of a suicide crisis that's defying the Pentagon's investment in prevention programs.

"It's not a deployment problem, because over 50 percent of the people that committed suicide in the Army National Guard in 2010 had never deployed," Maj. Gen. Raymond Carpenter, the acting director of the Army National Guard, said Wednesday at a news conference where the new figures were announced.

Carpenter also discounted the role that economic conditions played in the increase in suicides among reservists and members of the National Guard.

"Only 15 percent of the people who committed suicide in fact were without a job," he said.

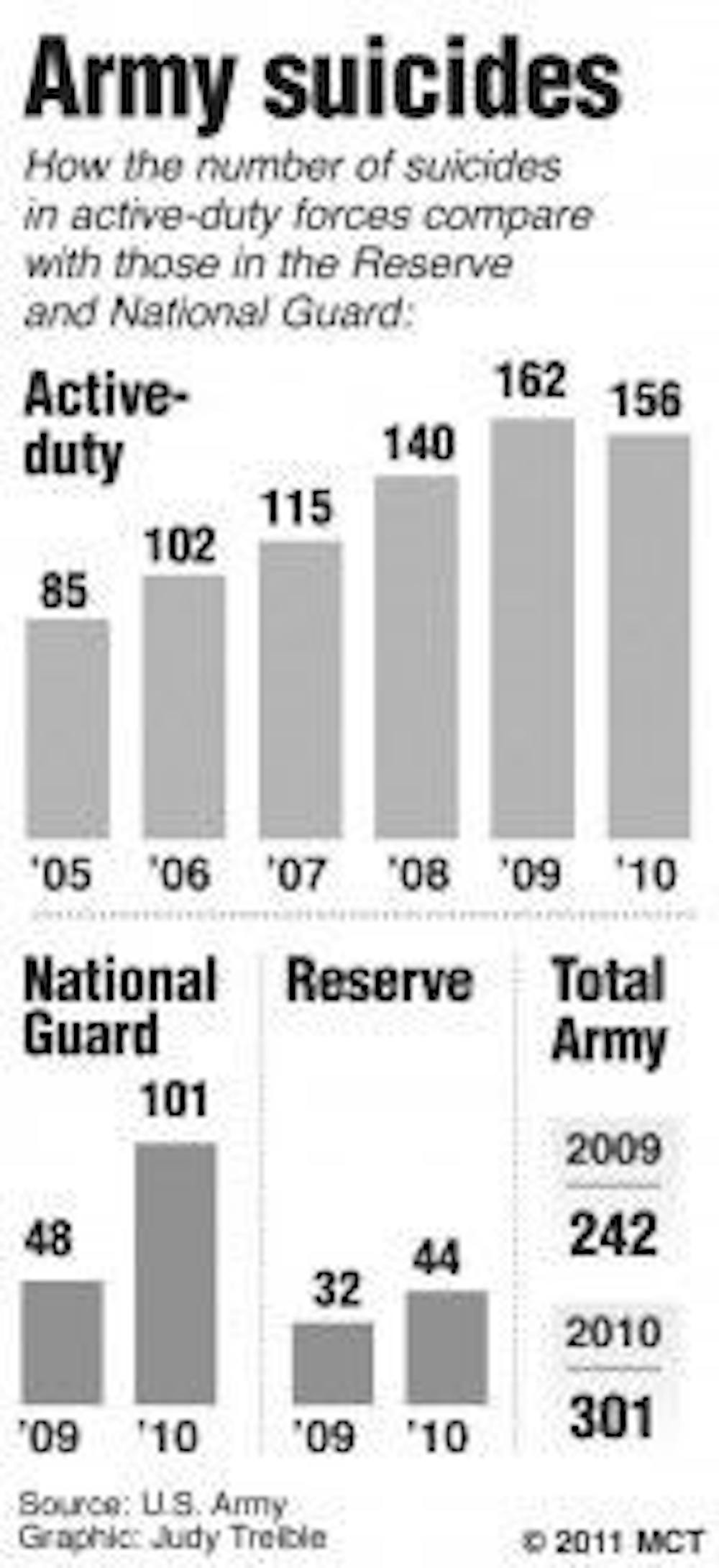

The Pentagon statistics released Wednesday listed 145 members of the Army National Guard and Army Reserves as suicides in 2010, up from 80 in 2009. Active-duty suicides totaled 156 in 2010, down from 162 in 2009, the Pentagon said.

Of U.S. military installations, Fort Hood, Texas, had the highest number of suicides last year, 22, compared with 11 in 2009. Fort Campbell, Ky., which had the highest number of suicides in 2009, 21, had 10 last year.

The Army's rising suicide rate, which last approached its current levels in 1990 and 1991, during the Persian Gulf War, has puzzled Army officials. Suicides hit their lowest levels in the last 20 years in 2000, when 63 soldiers killed themselves, according to Army statistics.

The Army has made suicide prevention a top priority. It's proposed shifting an unspecified part of proposed budget savings to suicide prevention programs next year, and soldiers now undergo training on spotting potential suicides among their comrades.

Soldiers receive resiliency training and post-deployment evaluations of their mental health, and Gen. Peter W. Chiarelli, the vice chief of staff of the Army, who's led the service's suicide prevention effort, is briefed on each suicide.

Chiarelli said he took some satisfaction from the drop in suicides among active-duty soldiers, and he credited the Army's emphasis on suicide prevention for that. Now, he said, the Army must expand its efforts to the Army National Guard and Reserve.

"I really believe we are leading an effort to destigmatize soldiers, family members, civilians (from seeking help) when they have these behavior health issues," he said. "They are injuries."

That, however, may be more difficult among these troops.

Unlike active-duty soldiers, members of the Army National Guard and the Army Reserve are part-time soldiers who have lives outside the military and often live hundreds of miles from the other soldiers in their units.

Carpenter, the Army National Guard's acting director, said failed relationships appeared to be the largest common factor in suicides.

"We have got to make the suicide-prevention plan a family plan, because it's that family that is with the soldier the other 28 days of the month," said Lt. Gen. Jack Stultz, the chief of the Army Reserve.

In mid-July, the Army released the results of a 15-month study of suicide trends.

That 350-page report absolved the repeated deployments of soldiers to Iraq and Afghanistan in recent years of responsibility for the increase in suicides, noting, as Wednesday's statistics did, that few of those who'd killed themselves had deployed more than once to a war zone.

It said that levels of illegal drug use and criminal activity in the Army had reached record highs, while the number of disciplinary actions and forced discharges were at record lows, and it suggested that tougher action against drug offenders might help curb the problem.

"Drug and alcohol abuse is a significant health problem in the Army," the study found.

Where the Army once rigidly enforced rules on drug use, it got sloppy in the rush to get soldiers ready for the battlefield, the report said. Officers who once trained soldiers on everything from drug abuse to financial planning had only enough time to get their troops ready for battle.

The number of misdemeanors that soldiers committed — including traffic infractions, drunken driving and being absent without leave — rose to 50,523 in fiscal year 2009 — a sign, the report said, that "good order and discipline" were declining in the ranks. Five years earlier, the number was 28,388.

Chiarelli conceded Wednesday that the Pentagon doesn't know what causes suicides, saying that each case is different. He said the Army was hamstrung because it couldn't investigate each recruit's mental health before he or she joined the military.

"If you want to join the United States Army, I look you in the face and ask you if you have ever had any mental health problems, and if you say no, that is basically it," Chiarelli said.

In spite of the evidence that deployments are unlikely to be the cause of suicides, Chiarelli said he was still hopeful that increasing the amount of time between deployments to two years for every year deployed would help solve this problem.

"I really believe (that) is one of the things we have to look at," he said.